This stance was conveyed by the regent in his remarks at a discussion of indigenous peoples held at the Toba Regency Regent’s office on Monday, October 3, 2022. From the verification and identification of indigenous communities such as Simenak-Henak, Natinggir, Natumingka, Matio, Sigapiton, Paria Dolok (Ombur), the Toba Regency Government stated that these six indigenous communities are not eligible to become customary law communities.

In the same speech, Regent Poltak said that indigenous peoples must be wiser about what they are fighting for. “If you want to fight for customary forests, you must understand that customary forests cannot become property rights, cannot be sold. Based on verification, the existence of indigenous peoples cannot be forced or made up,” he continued. The Regent proposed that the community apply for TORA which can become property rights and get certificates.

“So don’t say that the regent is not pro-people. As a regent, I just don’t want to break the law. And I don’t want to go to jail because of this. I cannot be like other regents who can issue customary forest decrees. If I want to establish indigenous peoples and customary forests, the community should first file a civil lawsuit to the District Court so that there is a permanent legal decision,” he concluded in his speech.

Toba District Legal Head, Lukman Siagian, also said that only 6 communities had applied. The district government first verified and then the MoEF formed an integrated team to verify 8 communities. He said that there were no submissions from the Janji Maria and Sigalapang Indigenous Peoples. “That’s why only 6 communities are shown on the screen. From our findings, there are many internal conflicts in the community and also boundary conflicts. Boundary issues must be explained in minutes. Customary institutions that take care of customary law are no longer found. Neighboring customary institutions that recognize customary boundaries do not have minutes. The ones who are competent in this process are the sub-district head and village head because they are more knowledgeable about the problems in the community,” he explained.

Furthermore, Lukman Siagian said that the district government did not dare to decide because there are two requirements, namely history and customary territory, out of five requirements listed in Permendagri No.52/2014 (download here) on Guidelines for Determining Customary Law Communities. “There are also outside indigenous peoples or new clans that have proposed and it needs to be questioned where they came from. Meanwhile, residents and village heads are not involved. The Raja Huta or Raja Jolo has a doubtful relationship with the land. The spatial planning also does not exist because it has become a concession,” he said.

On that occasion, Abdon Nababan questioned Murphy Sitorus’ statement as the regent’s expert staff in legal affairs and former Regional Secretary of Toba Regency who said that there were no indigenous peoples in Toba.

“I did not say that there are no indigenous peoples in Toba. But I said that there are no indigenous people in Toba Regency,” Murphy replied.

Abdon Nababan then explained that indigenous peoples are the same as customary law communities. “It’s just a matter of designation. It’s the same with the term communal rights, customary land, or customary territory. Communal rights is a Minang language which means a collection of authority and authority of customary leaders. Not just one person who determines. Many laws in this Republic regulate the object, but none regulate the subject. Actually, during the Dutch Presidency in Toba, there were already customary forests that were administered. But after Indonesia’s independence, this was no longer done. That means the Batak people are indigenous people,” he explained.

Huta Na Marmarga or Marga Na Marhuta (A village with a clan and a clan with a village)

Abdon Nababan said that if Batak people meet the rules, they ask each other 2 basic questions: “What is your clan?” and “Where are you from?” One’s clan hood will be doubted if one cannot answer them well. Both questions will show identity, territorial and genealogical ties.

“Indigenous peoples exist and live according to the times. If you look for indigenous people 300 years ago in Toba, of course, the Verification Team will no longer find them. Customary institutions today are also weak because of the presence of villages, religion, and positive laws. But weak does not mean non-existent. That is precisely what needs to be restored and strengthened,” Abdon explained.

The state has admitted to being negligent and ignorant about customary forests by Law No. 41 of 1999 which states that customary forests or rights forests are located within state forest areas. Constitutional Court Decision No. 35/2012 confirms that customary forests belong to indigenous peoples.

Toba Regency has already recognized the existence of indigenous peoples through Regional Regulation No. 13 of 2000 on the Empowerment and Preservation and Development of Customs, Customs and Institutions and Regional Regulation No.1 of 2022 on the Customary Rights of the Toba Customary Law Community. The current condition is a setback because there are already rules. Permendagri No. 52/2014 is no longer relevant to use because there are already 2 local regulations.

Abdon explained that in Permendagri 52/2014, the requirements for history and customary territories are mandatory. Meanwhile, customary institutions, customary law, and historical objects are considered complementary because they are dynamic.

“The use of jambar (party attributes that are generally meat) and ulos (typical fabric of the Batak people) is proof that customary law still exists. So if we look for something that doesn’t exist, we won’t find it,” said Abdon Nababan.

Toba Police Chief, Taufik, admitted that Abdon’s explanation was very interesting and wanted to study it. “There is a legal basis for defining unity. This means that both parties, namely indigenous peoples and the Toba Regency Government, need to first agree on the definition of indigenous peoples and customary forests. The indigenous people are forcing the district government to recognize indigenous peoples and customary forests while the district government does not want to collide with the law. If I may suggest, just invite the Ministry of Home Affairs here to sit together to equalize understanding and find a good solution,” he said.

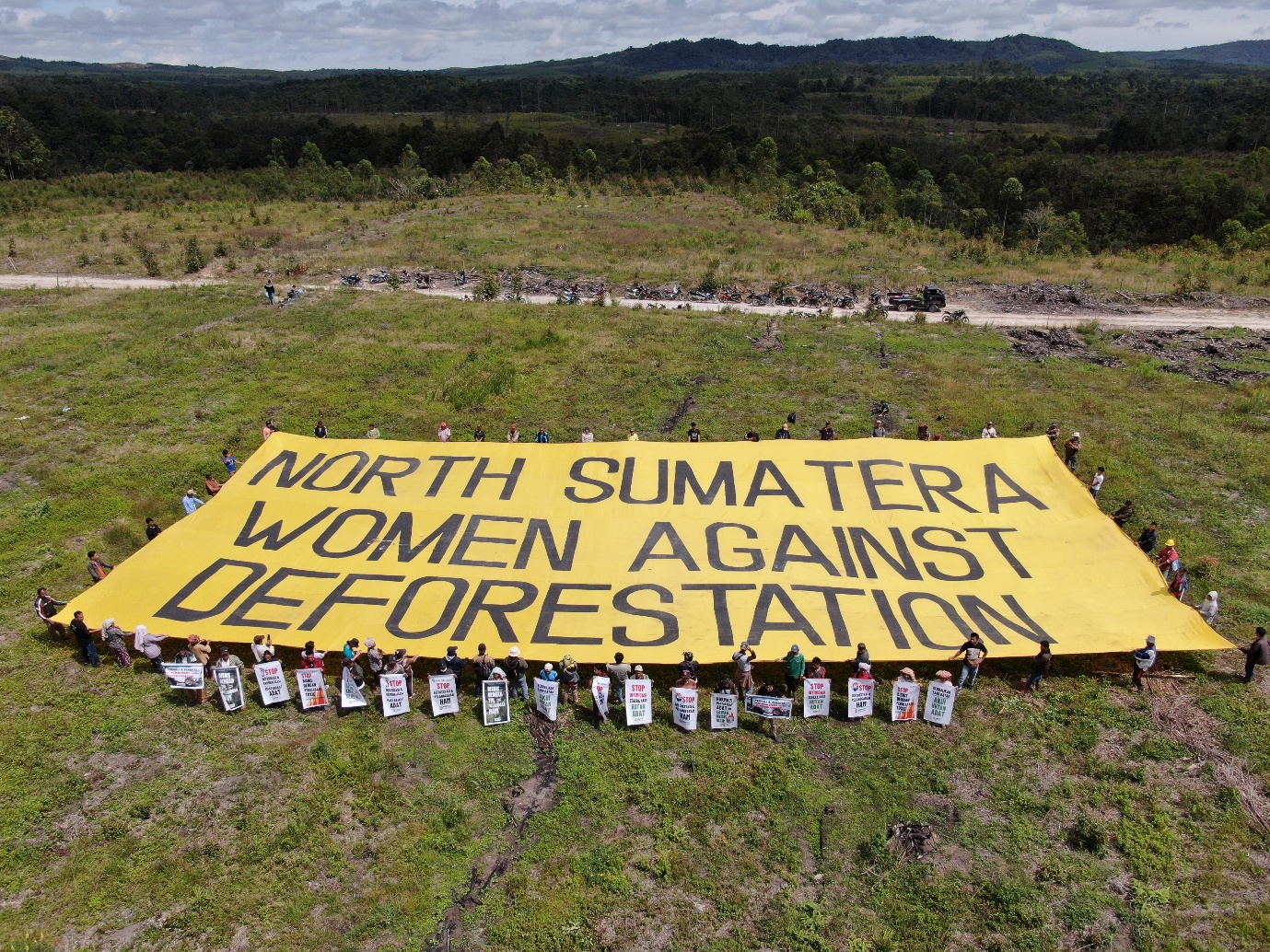

Menti Pasaribu, an indigenous woman from the Natinggir community, demanded legal certainty for them as farmers. “We want security on our land. We want sovereignty over our customary territory. We are not tenants but legitimate voters of the customs territory of Pomparan Op. Raja Nasomalomarhohos Pasaribu. Seven members of our community were summoned by Toba Police. We are not criminals, but only want our customary forest to be preserved and help improve the climate for our lives and the world. We only live from agricultural products in our customary territory,” said Menti Pasaribu.

The discussion agreed to conduct a legal consultation between the Ministry of Home Affairs, academics, indigenous communities, and the Toba Regency Government soon.

The discussion was attended by the Toba Regent, Toba Police Chief, KPH IV Balige, Balige District Attorney, Abdon Nababan, KSPPM, AMAN Tano Batak, BPN, Natinggir Indigenous Peoples, Indigenous Peoples of Janji Maria, Lintong, Matio, Natumingka, Simenak-henak, Sigalapang, Parria Dolok Ombur, Regional Secretary, Head of Law of Toba Regency, Sub-District Head of Borbor and Simare Village Head. At the end of the discussion, the Indigenous Peoples of Pomparan Ompu Raja Enduk Pasaribu submitted documents requesting the determination of Indigenous Peoples and Indigenous Forests to the Regent of Toba witnessed by the discussion participants.**